Since its founding in 1969, the Festival Panafricain du Cinéma et de la Télévision de Ouagadougou – popularly known as Fespaco – has built a reputation as Africa’s most important film festival. Earlier this year, a panel of key Fespaco contributors convened in London to honour the festival’s legacy. Nadia Denton, the driving force behind the ‘Beyond Nollywood’ initiative, was present to capture the highlights.

or over five decades, Fespaco has been the premier arena for reaffirming and celebrating Africa and its global diaspora on the big screen. Widely regarded as a site of pilgrimage among filmmakers and industry figures from the African diaspora, the Burkina Faso-based festival’s cultural significance is due to its status as a truly pan-African space to discuss, debate and analyse the problems confronting modern African cinema. “Nowhere are so many African films shown at once; nowhere do so many African filmmakers ever come together,” remarked the influential Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, a founding father of the festival, which, at its peak in the pre-Covid years, attracted more than 500,000 local and international spectators.

Government-organised since its inception, Fespaco has been beset with challenges over the last decade: problems with curation, event management, marketing and promotion have risked alienating festival-goers, threatening Fespaco’s reputation as the greatest film festival on the African continent. Yet many still loyal to the pan-African ideals upon which the festival was founded continue to strive to restore it to its former glory. Among them is Black Film Bulletin founder and film archivist Dr June Givanni.

In the summer of 2023, the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive enshrined the memory and legacy of Fespaco in an exhibition named ‘PerAnkh’, a showcase of the Archive’s treasures, hosted at the Raven Row gallery in London. A series of events ran alongside the exhibition; of particular note was a panel discussion titled ‘Fespaco and the Archiving of African Cinema’, which assembled such African industry luminaries as the filmmakers Mohamed Challouf and Jihan El-Tahri and the curators Aboubakar Sanogo and Keith Shiri. Chaired by Givanni, the conversations recounted in dramatic detail the highs and lows of Fespaco, giving both personal and professional context to the history of the festival, which in recent times has drawn increasing criticism from the filmmaking community it set out to serve. The spirit of Fespaco was ever-present, with lively, provocative outbursts from panelists and audience members alike – “Fespacoesque”, as El-Tahri put it.

El-Tahri, who is Egyptian, shed light on what made the 50-year-old festival so unique for African filmmakers, passionately describing it as “the only place where people from the Global South have their own space: we are not visitors there, we can talk together, there is a sense of safety – we are not being judged. We can be who we are in our different articulations, languages and aesthetics.” Irrespective of its flaws, Fespaco still rivals many lauded Western festivals in the minds of film practitioners from the Global South.

Reflecting on Fespaco’s intentions towards African filmmakers and the extent of its decolonial ambitions, El-Tahri remarked: “In the francophone African colonies, the ‘image’ was forbidden to the ‘natives’. [These restrictive strategies existed in anglophone territories too, and were referred to as ‘specialised technique’.] It was not until the early 1960s [albeit decades earlier in Egypt] that the idea of who we were as Africans was transmitted through our own eyes in dramatic feature films… we could represent and film ourselves. The way that external powers could control that space was by stopping the funding and distribution, and that was what Fespaco tried to break.”

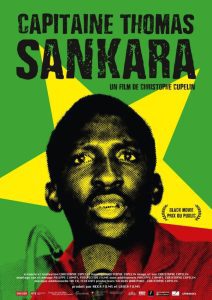

Capitaine Thomas: Sankara

In the 1990s, the festival began to encompass a younger generation of filmmakers, moving beyond the dominance of the old guard. “These founding fathers [such as Ousmane Sembène] were always there, but there was little engagement with the younger generation,” recalled El-Tahri. “Then, in 1995, there was a movement to have a stronger voice from the second generation, and the Guild of African Filmmakers in the Diaspora was created. Most of us rarely had our films shown in our own countries, and so a lot of African filmmakers who were part of the Guild were those making films that would compete internationally.” To ensure it maintained its pivotal platform on the continent, Fespaco had to embrace changing demand.

Shiri, a UK-based curator originally from Zimbabwe, spoke of the importance of the grammar of African cinema and the fact that it arose from a revolutionary politics rooted and present in other forms of African artistic expression, such as the paintings of the Oshogbo school in south-west Nigeria and the music of Fela Kuti. Shiri insisted that such evolution occurs via cultural immersion in an African festival like Fespaco; knowledge of this underpins the loyalty many in the wider African film community have felt in standing by the event even during its more difficult phases.

The idea of Fespaco as a site of cultural exchange was expanded on by Sanogo, associate professor in film studies at Carleton University, Ottawa, who argued that the festival has long been “a liberated zone for African filmmakers to show themselves”. Sanogo described Fespaco as “an emancipatory project; something that pertained to and exceeded cinema. It was born in conversation with a large group of theorists and thinkers who were trying to address a number of questions: can we have an African culture if we are colonised? When we get rid of colonisation, what kind of culture and politics of culture could we have?”

Evidently, over the years, the festival has created fertile ground for the formation of a new kind of Afrocentric filmmaking consciousness, influencing generations of filmmakers from the continent and beyond. Reiterating the festival’s multi-dimensional potency, Sanogo posited that Fespaco has functioned as an incubation space, “the intellectual and cultural framework within which the pioneers of African cinema emerged”. But he also pointed out that “as part of this pan-African movement, the filmmakers and artists had a defined set of responsibilities. There was a sense that the filmmaker knew less than ‘the people’ but was accountable to ‘the people’.”

Looming large in the panel’s consideration of the history and legacy of Fespaco was the late Burkinabe leader Thomas Sankara. A committed Marxist revolutionary, Sankara came to power via a military coup in 1983. Known as a ‘man of the people’, Sankara struck out at corruption and promoted an anticolonial vision for a Burkina shaped by its own needs, prioritising self-determination, childhood health and women’s rights. He saw potential in the pan-African ambitions of Fespaco and embraced it wholeheartedly.

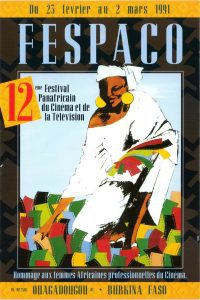

Poster for the 12th edition of Fespaco, 1991

Sankara’s reputation as something of an African Che Guevara made attendance at the festival even more attractive to filmmakers and artists who saw themselves as part of a pan-African film movement. But in 1987, at the age of 37, Sankara was killed in another coup led by his former friend and co-revolutionary Blaise Compaoré. During Compaoré’s rule, which lasted until 2014, Challouf’s 2000 documentary about Fespaco, Ouaga: Capital City of Cinema, was banned – though it was eventually shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato on the 50th anniversary of Fespaco in 2019, and was also screened at ‘PerAnkh’, along with the films FESPACO ’87 (Carolyn Sides, 1987) and Ouaga: African Cinema Now! (Nii Kwate Owoo & Kwesi Owusu, 1988).

According to Challouf, the purpose of both Fespaco and the Carthage Film Festival in Tunis, which was founded in 1966, was not merely to screen films but to create a whole ecology of cinema distribution and exhibition, and challenge the domination of other nations’ films on African screens. Tunisian film critic Tahar Cheriaa, who founded the Carthage Film Festival, was briefly imprisoned in 1969 for his efforts to get distribution and exhibition nationalised in countries across the continent to create market space for African films. Challouf noted three landmark films that were stifled by lack of finance from Northern hemisphere partners uneasy with the histories being recounted: Amok (Souheil Ben-Barka, 1983), Sarraounia (Med Hondo, 1986) and Camp de Thiaroye (Sembène, 1988). Sankara provided key support during the production of Sarraounia, allowing the film to be shot in Burkina Faso when the government of Niger withdrew its support, likely following commercial pressure from France.

Evaluating Sankara’s influence on Fespaco, Sanogo stated that the leader’s support for the event was “one of few instances on the African continent where the vision of filmmakers and the vision of the state merged. It was magical.” He continued, “There is a ‘dream deferred’ dimension which is still haunting African cinema… [During Sankara’s time] there was a clear vision… an ideological spectrum of possibility that was counter to capitalism… many of the pioneers were comrades.”

Challouf, too, was unstinting in his praise of the radical figure: “Thomas Sankara did the most for African cinema.” Many veterans in the wider African filmmaking community have refused to return to Fespaco since Sankara’s assassination, considering attendance to be a betrayal of the progressive vision he stood for. During the panel discussion, the acclaimed Ghanaian British filmmaker and visual artist John Akomfrah, who was in the audience, commented: “Fespaco is difficult to talk about for many of us because of the spectre of Thomas Sankara. The festival was a place of maximum promise as well as the biggest tragedy. There was a Promethean ethic behind Sankara’s project, and that ethic assumed that you as the national leader could control the national culture; that you had enough control over the cultural means of transmission to do something and make a real effort. The neoliberal project has put an end to that. There is no African leader anywhere on the continent who even has the illusion or hubris to assume they have any control over their national culture. Sankara’s will to do something about the national culture chimed with ours [as African filmmakers].”

In another impassioned audience interaction, filmmaker Kwesi Owusu offered a counterpoint to the romanticism expressed about the revolutionary: “It was very exciting being there around that time with Sankara… but we idealise that period a bit too much. I think that after so many years we need to step back and look beyond what that represented. We need to look more critically at the military intervention. Sankara had a powerful human face, which softened the harshness of that reality, which was very brutal in many ways.”

The panel concluded with reflections on how to fertilise the memory of Fespaco for future generations. A new future for the event needs to be written, should it last another 50 years. Sanogo underscored the conceptual importance of exhibitions like ‘PerAnkh’ with a clarion call: “We must all contribute to the work of transmission and be actors/curators of the memory of the future, as we are in a period when this memory is being lost, or can be lost, to the contemporary interpretation of cinema.” On preserving the pan-African idealism at the heart of Fespaco, El-Tahri affirmed: “It is one of the last remaining spaces where the idea of pan-Africanism is engaged with on the ground; it is concrete. You sit with people you would never meet anywhere else. You engage with them on a cultural level and many, many projects get off the ground in that space.”

The second entry in the three-volume book series African Cinema: Manifesto and Practice for Cultural Decolonisation, published in August by Indiana University Press, is devoted to Fespaco. Edited by Burkinabe filmmaker Gaston Kaboré and professor Michael T. Martin, and containing contributions from a significant cadre of filmmakers, critics, academics, curators and industry leaders from around the world, it provides a critical and timely resource for reflection on African cinema and its history at Fespaco and beyond. So it would seem that the blueprint for the festival’s continuation holds promise. Or, as Fespaco’s former director-general Michel Ouédraogo put it in a 2009 interview: “Fespaco’s founders made it a pan-African, continental tool. The challenge today is to make it an international tool. The final goal is for Fespaco to become the most important institution of African cinema: if it can combine its political institutional mission and that of creating an event that resonates throughout the world, Fespaco will have achieved its full goal.”

Sign up and stay informed of my forthcoming events.